Editor’s Note: This is part one of a column putting U.S. immigration in historical context.

Even in a country founded in rebellion and based on a Constitution that calls for promoting “the general welfare” – for securing “the blessings of Liberty” — a walk down the hall of mirrors that is history reveals many chapters when fear (of change; of “the other”), ignorance, and hatred reigned supreme and pushed aside what Lincoln called “our better angels.”

In his new book, The Soul of America, the historian John Meacham writes that, “Anxiety about refugees and immigrants and the related desire of presidents to quell that unease were then—and have always been—an element in the American experience.” The most infamous of these legislative prohibitions was the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. But there have been many attempts to pull up our gangways, close our borders, and keep certain “types” from becoming part of the American dream.

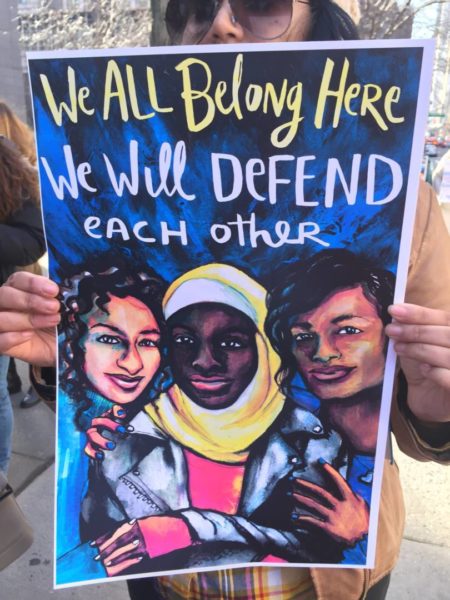

On Saturday, June 30, as coast-to-coast protesters flooded the nation’s streets, chanting “We are better than this,” it’s important to look to our history and examine those ugly times when hate and division gained the upper hand and what we can learn from them. Since, as California Senator Kamala Harris put it to protesters rallying in LA: “We are at an inflection point.”

In the 1920s, the immigration debate was fueled by the pseudoscience of eugenics. Its proponents argued that character was inheritable and that some ethnic groups were superior to others—having evolved to a greater degree. In their book, These United States: A Nation in the Making – 1890 to the Present, the historians Glenda Gilmore and Thomas Sugrue trace the course of immigration “reform” over decades. In the 20s, Anglo-Saxons were grouped with other northern Europeans “into a category called the Nordic races.” This was in reaction to the swelling numbers of immigrants entering the country from southern and eastern European countries. Donald J. Trump is not the first American to call for “more Norwegians.”

The National Origins Act of 1924 did several things: it set an annual number for immigrants entering the United States. It set quotas at no more than 2 percent of what the U.S. total for each nationality had been in 1890 – before the influx of Catholics from southern and eastern Europe. Meanwhile, agribusiness in California lobbied for maintaining a seasonal Mexican labor force.

The resurgent Ku Klux Klan adopted the slogan, “America for Americans” and added anti-Catholicism and anti-Semitism to their “program of hate.” And, as Gilmore and Sugrue write: “On a hot July 4 in Kokomo, Indiana, in 1923, more than 100,000 people drove their flag-draped family cars to Melfalfa Park for a rally.” Their description goes on in chilling detail, about the growth of the Klan. However, even as it dwindled, “hatred continued to smolder in those ashes.”

In 1965, when Congress passed the Hart-Cellar Act, it was the “most sweeping immigration reform in decades.” But even as it lifted quotas and “changed the complexion of immigration to the U.S., it had other, unintended consequences,” specifically, for immigration from Latin America.

Part II of this column — “Yearning to Breathe Free” – will look at the consequences of the immigration reform acts of 1965 and 1986 on our Latin American neighbors. Meanwhile, in 2018, we are at an “inflection point” – a time to decide which direction our nation’s moral compass will point.