Editor’s Note: This story has been updated to include a statement we received from UMEC owner John Catsimatidis after the original article was published April 28.

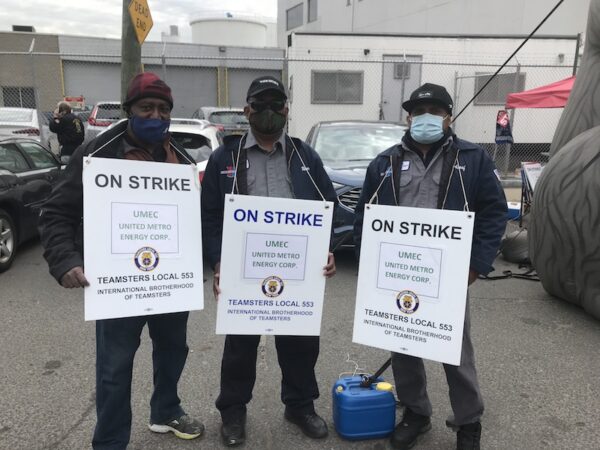

NEW YORK, N.Y.—After more than two years trying to win a first union contract, 24 workers at the United Metro Energy Corp. fuel distributor in Brooklyn went on strike April 19. The company, owned by billionaire supermarket magnate John Catsimatidis, retaliated by firing three of them, Teamsters Joint Council 16 said.

“They fire people at will. I’m easier to get rid of than the copper,” André Soleyn, a terminal operator and father of three who was sacked the day the strike began, told LaborPress at a rally outside the United Metro terminal in Greenpoint Apr. 27.

Two more workers were fired on the 20th and the 26th, according to the Teamsters, and the company did not give a reason.

Once, when a manager was fired, Soleyn says the company hustled him out so fast he had to leave his glasses behind. With a union contract, he added, they’d be protected by a grievance procedure.

“There must be some kind of oversight to this firing,” he said. “It makes for low morale.”

The strikers are terminal operators, truck mechanics, and service technicians who voted to join Teamsters Local 553 in February 2019. But the Catsimatidis lawyers negotiating for United Metro, says Local 553 secretary-treasurer Demos P. Demopoulos, are “reluctant to come into the pension” or commit to having workers be covered by the Teamsters’ health-benefits plan.

“They’re trying to cut out the pension,” former Joint Council 16 president George Miranda said. “That’s what it comes down to all the time. It’s a profitable company.”

Workers now have only a 401(k) plan, and United Metro matches half of what they contribute to it, up to 3% of their annual salary, according to a Local 553 official. The company bills itself as “the leading energy provider in the New York Metropolitan Area and Long Island.” It also has a terminal on Long Island Sound 80 miles east of the city, and is building a biodiesel plant in Brooklyn.

He added that the company had already offered “certain common-sense solutions,” including participating in the Teamsters’ welfare plan “and additional retirement benefits for our employees.”

Catsimatidis denied that the company had “retaliated” against the striking employees by “firing” them, saying it was legal to hire strikebreakers as permanent replacements.

“No striking employee has been fired,” he said. “A few employees have been permanently replaced since we need to be able to continue our operations because our customers depend on us. Our customers include hospitals, schools and first responders, and we must continue servicing them regardless of any ongoing labor dispute. As much as the union has the right to strike, we have a right, under federal labor law, to permanently replace employees to enable us to service our customers. That’s a fact!”

About 75 people, a mix of strikers and members of other Teamsters locals turned out to join the picket line outside the Greenpoint terminal, across the street from the giant metal onions of the city’s sprawling sewage-treatment plant, in the industrial area on the banks of Newtown Creek. Dump trucks and fuel-tanker trucks passed by on Kingsland Avenue, their drivers honking loudly in support.

Strikers say their main issues are higher wages, better health-care coverage, respect, and less irregular hours. “More pay, better insurance, better treatment —everything,” said truck mechanic Dennis Spence of Brooklyn.

They are paid far less than the city norm for the fuel industry, according to the Teamsters: They start at $16.80 an hour and go up to $27.50, while union scale is $36.96 plus a pension.

“We’re the lowest paid in the whole industry,” said Chris, another terminal operator, who did not give his last name. “You go down the block and they get paid forty, fifty percent more than us, and we do the same work.”

They also haven’t gotten a raise in three years, says Radouane, a Moroccan-immigrant truck mechanic known as Rocky.

The company gives only six paid holidays a year, added Chris, and workers called in on holidays often have to do 12-hour shifts.

United Metro workers are paid far less than the city norm for the fuel industry, according to the Teamsters: They start at $16.80 an hour and go up to $27.50, while union scale is $36.96 plus a pension. “One day we work late, the next you get sent home early,” said Ramesh Hardowar, a widowed father of two from Queens who has worked as a service technician and installer at the company for 14 years.

Going out to repair heating systems and boilers is often dangerous, he said, with rats in the cellars — some alive and running, some dead — and asbestos from decrepit old insulation, but “we have to go, because we have the contract. That’s our pride, make the customer happy.”

Another complaint is that the company’s health plan has high copayments and such a narrow network that few medical providers accept it. “You go to the eye doctor, insurance don’t cover nothing, and it’s hard to find people who take it,” said Spence.

The terminal distributes gasoline, diesel fuel, biodiesel, and heating oil to customers that include city public schools, hospitals, gas stations, and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. The fuel arrives by pipeline, trucks, and barges.

Terminal operators’ job, Soleyn said, is to make sure the fuel is stored properly and that the systems are working properly. They’re also trained to handle security.

Two of his three daughters are in college. “Every weekend, I have to write out what I can spend. I want to be able to afford them a dream,” he said. “Am I providing for my girls? That’s what I’m striking for.”

Another bargaining session is scheduled for Wednesday, May 5.